From the 5/21/2021 newsletter

Director’s Corner

The Hogwarts Model: Putting it all Together in Learning Communities is Foundational to the New Medical School Curriculum

Adina Kalet, MD MPH

Dr. Kalet discusses how MCW’s Learning Community (LC) model has the potential to benefit students and faculty members, addressing our desire to build character and caring, while strengthening both academic and social opportunities for our learners …

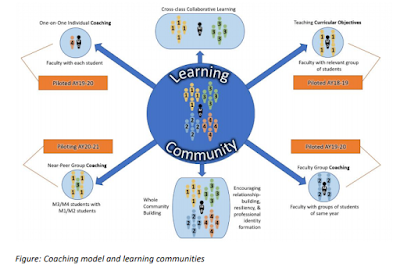

Last spring, in anticipation of a rough, rapidly evolving, and socially isolating year, the MCW School of Medicine built a learning community (LC) structure for the entering M1 class to ensure social cohesion and engagement. We wanted students to weather the pandemic with regularly scheduled and academically meaningful structured connections with their peers and between students and faculty members. We accomplished this by weaving together the required REACH (Recognize, Empathize, Allow, Care, Hold Each Other Up) Curriculum and the voluntary 4C Academic Coaching Program. We wanted the students to experience a sense of continuity and have sufficient time to establish true collegiality and strong bonds through “cyberspace.”

A targeted, sophisticated faculty development process was devised and implemented to train over seventy MCW faculty and staff and twenty-seven students to be leaders. Now, a year later, we are in the process of analyzing the data and can report that the experiment was a success. Preliminary student feedback is inspiring. Similar to experiences at other schools with LCs, the participants report that they gained a great deal. The LC has become a central component of the evolving proposal for the new MCW medical school curriculum.

This issue of the Transformational Times describes the process and amplifies the voices of both students and faculty participants. I hope you will read the descriptions and enjoy the personal stories they share.

"It matters not what someone in born, but what they grow to be."

– Professor Albus Dumbledore

The most well-known learning community model is Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, that secondary boarding school administered by the British Ministry of Magic in an unlocatable spot in the Scottish Highlands. Upon arrival at Hogwarts, new students are assigned by the sorting hat - based on a magical mash up of personality, character traits, and a bit of “destiny” – to one of the four houses, Ravenclaw, and Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, or Slytherin, named for their founders. Just in case you are one of the few people alive who doesn’t know what I am talking about, read the seven volume Harry Potter series by JK Rowling for more details (or watch the movies). You will learn that once assigned to a house, students are pretty much set for years of mostly healthy academic and athletic competition and a great deal of intrigue. At Hogwarts, as in many idealized academic settings, students develop lifelong bonds with housemates by studying, eating, living, and having innumerable terrifying adventures together.

This identity setting framework is very important to individuals and to the whole Wizarding community. Increasingly, medical schools - as well as many other higher education environments – are embracing this rather “ancient” model to redress the persistent concerns about lack of academic continuity and inconsistent mentoring, and to provide the healthy social connections that enhance lifelong resilience.

What are Learning Communities?

Learning communities are not “extracurricular,” but fully integrated foundational components of the curriculum. Each LC is a group of people who share common academic goals and attitudes and meet regularly to collaborate on learning activities. While it has all of the “student life” benefits in common with advisory colleges, “eating clubs,” dorms organized by affiliations, sororities, or fraternities, an LC goes well beyond simply providing a rich social structure. They are best thought of as an advanced pedagogical design. Medical schools around the world are adopting this model, the highest profile among the early adopters have been Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

Rather than considering the individual learner as the only relevant unit of instruction and performance assessment, these “communities of practice” explicitly acknowledge that education is a shared cultural activity with a significant communal component. This sociocultural approach is not a new idea, but it remains a challenge to implement effectively. At its best, the LC model provides a means to structure medical education in truly relationship-centered - as opposed to course-centered – ways.

In our proposed LC model, academic coaching is fundamental. This inextricably links the cognitive and non-cognitive components of learning on the road to becoming a physician, and put relationships among members of the community at the center of that learning and professional identity formation.

As part of the Kern Institute’s Understanding Medical Identity and Character Formation Symposium (see my Director’s Corner on April 30, 2021), a group of national leaders discussed “The Nature of Learning Communities and the Goals of Medical Education.” David Hatem, MD (University of Massachusetts), William Agbor-Baiyee, PhD (Rosalind Franklin University), Maya G. Sardesai, MD MEd (University of Washington), and our own Kurt Pfeifer MD, explored how their LC structures explicitly address students’ acculturation to both medical school and the profession of medicine. They reported how a healthy learning environment counters the noxious impacts of the “hidden curriculum,” while supporting students on their professional journeys during medical school, aiming to ensure that students are ready for, and will thrive in, a lifetime of practice as a physician.

The panelists also shared the collective experience of the forty-seven medical school members of the Learning Communities Institute (LCI), reviewing the essential characteristics LCs must possess to foster character, caring, and the development of a mature and hardy professional identity. These include:

- Committing dedicated medical school resources and time in curriculum

- Assigning buildings or spaces that allow students to gather to form relationships (Johns Hopkins constructed a building dedicated to their learning communities)

- Aligning espoused professional values with values that are practiced by promoting the skills of doctoring while intentionally countering the learning climate’s unsavory elements and its hidden curriculum

- Promoting longitudinal relationships between mentors and students from beginning to end of medical school, thus enabling mentors to simultaneously support learners while holding them to high professional and academic standards

- Supporting character formation through peer mentoring programs and career decision making

With these guidelines to inspire us, and seeking the collaboration with and approval of the MCW’s Curriculum and Evaluation Committee and the Faculty Council, we intend to build LCs tailored to our institutional culture and strengths. For more, see the essay in this week’s newsletter entitled, “Learning Communities at MCW – A Vision for the Future.”

The critical importance of continuity - Putting it all together

Throughout my career as a medical educator, I have been involved in efforts to structure close student-faculty engagement and mentoring through small group learning structures. This has included decades of teaching in small groups in an introduction to clinical medicine course for M1 and 2s and being an Internal Medicine “Firm Chief” responsible for successive cohorts of clinical clerks (M3s) while leading an Advisory College style program. These learning structures have often been profoundly satisfying for students, my colleagues, and for me as we provided meaningful educational experiences and mentoring. But none of these experiences provided students with truly longitudinal - admission to graduation - integrated coaching or mentoring. I always knew we could be doing better. I fully believe that the LC model promises a real opportunity for the continuity the current system lacks.

There is benefit to the faculty, as well

There is no better way for faculty to develop wisdom as medical educators than by committing to a longitudinal process. I started my career focused on residency education and got to know wave after wave of trainees as individuals. These relationships showed me the common developmental trajectories and predictors of success or failure and, therefore, made me a more patient, accurate, and persistent coach. For example, I noticed that the first year residents who worked most slowly in clinic, staying later than peers to finish their patient care sessions, often grew into skillful and efficient clinicians, and were more likely to be eventually selected as chief residents. Knowing this made me more patient and kept me from “taking over” to get their patients “out the door.” I let the novices struggle a bit, confident that their patients were receiving better, more attentive care. It was personally rewarding to know that my patience helped to nurture some wonderful, future colleagues, but I only knew this because I had provided years of longitudinal mentorship.

Medical school should be a guided experience toward a life in medicine. Learning communities offer a framework for “putting it all together,” providing solutions to many of our modern challenges in medical education while enabling the magical relationships with the student’s peers and faculty. Our goal is to create opportunities for discovery and growth because, as Professor McGonagall once noted, “We teachers are rather good at magic, you know.”

Adina Kalet, MD MPH is the Director of the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Institute for the Transformation of Medical Education and holder of the Stephen and Shelagh Roell Endowed Chair at the Medical College of Wisconsin.