From the January 21, 2022 issue of the Transformational Times (Urban and Community Helath)

We Belong to One Another: A Lesson from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Cassie Ferguson, MD

In his letter he wrote from a Birmingham jail—the letter that began in the margins of a smuggled newspaper and on found scraps of paper—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. shared this:

“Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. And you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be—this is the interrelatedness of life.”

The very same stardust

Dr. King suggests that if we would see how inextricably connected we are to one another—if we would see that we belong to one another not only by virtue of being born on the same planet, but also by virtue of the scientific and spiritual reality that we were made from the very same stardust—that then all of us could see how the systems that uphold and protect racism, health and wealth disparities, educational inequalities, and residential segregation dehumanize us all.

That if we understood our interdependence, we would move beyond empathy for those who are suffering the most under the weight of these systems and know in our hearts that when one teenager is murdered, we are all killed. That when a pregnant woman delivers a stillborn baby because her health concerns are dismissed, that we all lose a child. That when one of our students must repeat their first year of medical school because of inequities in medical education and in our learning environment that disproportionately impact students underrepresented in medicine (URiM), that we all fail.

Dangerous unselfishness

This kind of radical compassion is not for the faint of heart. Dr. King understood this. In his very last speech delivered in support of the striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, Dr. King rallied the crowd declaring, “either we go up together, or we go down together. Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness.”

At the Kern Institute, our mission has been to inspire and support this kind of unselfishness and this kind of compassion in our learners and educators, such that we might transform the system of medical education to ensure that every one of our patients feels seen and deeply cared for; such that every one of our patients is given the opportunity to flourish. This kind of systemic transformation requires tremendous courage, sacrifice, and love. It demands that we understand compassion not “as a relationship between the healer and the wounded…but as a relationship between equals.” (Pema Chödrön).

Despite these challenges, there are examples of how the MCW community is “showing up.” Here is one example. In the spring of 2020, student doctors British Fields, Jamal Jarrett, Morgan Lockhart, Enrique Avila, and Adriana Perez learned that the Apprenticeship in Medicine (AIM) enrichment program they had been chosen to lead that summer would not be funded because of the pandemic. Led by the incomparable Jean Mallet and supported by the Kern Institute, these students advocated for their program, pivoted, and in three weeks designed and stood up the Virtual Health Sciences (VHS) program. Over Zoom, they provided forty Milwaukee-area high school students from backgrounds historically underrepresented in medicine a meaningful and engaging look at careers in health care and showed them that there is a place in the profession of medicine for them. Our student doctors saw themselves in these high school students and this motivated and empowered them to take direct action.

“The Path of Joy is Connection”

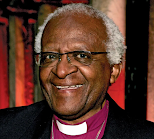

What I have come to realize as a physician and, as someone who teaches medical students about well-being, is that when we become aware of our interrelatedness, we not only wake up to how we might design and redesign systems that assume the humanity of all peoples, but we also feel less alone, less fragile, less anxious; and, like these student doctors, we are empowered to become our best and truest selves. As the late South African anti-apartheid leader and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu reminded us frequently, the path of sorrow is separation, and the path of joy is connection.

This week, as we celebrate the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., may we cultivate the awareness of our interrelatedness in our hearts, and find the courage to unselfishly redesign our world such that all of us may flourish.

Catherine (Cassie) Ferguson, MD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics (Emergency Medicine) at MCW. She is the innovator of the REACH Curriculum, and the Associate Director of the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Institute for the Transformation of Medical Education.